It is time “We the People of the United States” hold our elected and appointed officials to this rigorous standard

Matt Shipley - CFP - h/t to Victoria Baer

Most Americans incorrectly believe Supreme Court Justices are appointed for life and therefore somehow immune from public accountability, but this understanding is contrary to the Constitution and detrimental to our Republic.

Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution states, “The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behavior.” Accordingly, it is for a term of good behavior our federal judges hold their office, not life, and they can be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.

Misdemeanors, as the founders defined them, includes attempts to subvert the Constitution through misinterpretation or other methods. George Mason explained that impeachment is for “attempts to subvert the Constitution,” and Elbridge Jerry considered “mal-administration” as grounds for impeachment. Justice Joseph Story listed, among other reasons for impeachment, “unconstitutional opinions” and “attempts to subvert the fundamental law and introduce arbitrary power.” Alexander Hamilton and Justice Story defined “misdemeanor” as “mal-conduct” and Justices James Wilson and Story described “misdemeanors” as “non-statutory”, which means they are offenses for which no legal code exists.

From all these definitions and descriptions, it is clear the Constitutional framers intended misdemeanors to cover acts of political misbehavior, because the framers wanted to ensure every elected and appointed official at the national level is accountable to the people.

A common legal maxim maintains all contracts are to be construed according to the meaning of the parties at the time of making them. To interpret any contract contrary to its originally understood meaning is deceitful, subversive and criminal.

When the State ratifying committees and the private citizens of each State debated ratifying the Constitution, they did so under a commonly understood meaning to its words and clauses. Eventually, all thirteen original States ratified the Constitution and joined in union not only for their generation, but on behalf of all future generations.

Federal judges who interpret the Constitution in a manner that distorts this original intended meaning are altering the Constitution by circumventing the amendment process in Article V, which is a breach of our national contract. Any time the Constitution is changed, it is to the advantage of one group of people and to the detriment of another, because any change would either add another requirement to, or take away liberty from some group in society. If this is done without three fourths of the States agreeing to a change it is a despotic “encroachment and oppression” upon those it disadvantages, which is an illegal act deserving of punishment.

This criminal behavior is not just limited to purposeful misinterpretation of the Constitution, but extends, as pointed out by Justice Story, to referencing a different source of law other than what our founders used in establishing the Constitution and in defining boundaries to rights that are contrary to the understanding of that law.

Common law, as defined by William Blackstone, was not only the foundation of the American legal system, it was the Rosetta stone by which every American during the founding era understood law. As such, every word and clause in the Constitution, unless otherwise stated in the document, must be interpreted according to this pre-constitutional common law.

It is a non-statutory criminal act for those in public office, who swore an oath to uphold the Constitution, to reference another source of law or limit or extend rights based on other principles than pre-constitutional common law. For example, when considering the subject of torture, Justice Ginsburg referenced foreign law in her opinion and for this reason alone, she should no longer be on the bench.

To some, breaking “the supreme Law of the Land” may seem like an irrelevant procedural offense, especially if one likes the change. The danger in this is that it sets a bad precedent and when a change is made that people do not like, they have very little to no legal recourse to correct it.

If we, as a nation allow elected and appointed officials to violate the Constitution through its misinterpretation then every law in our nation will be viewed in the same way and law will be used against the people instead of for them. This is why the President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, who have taken an oath to uphold the Constitution, must be held to a rigorous standard of Constitutional interpretation based on original intent. Accordingly, if Supreme Court Justices and Federal judges cannot logically support their opinions by connecting them to constitutional original intent or pre-constitutional common law and refuse to change them, then they need to be impeached and found guilty.

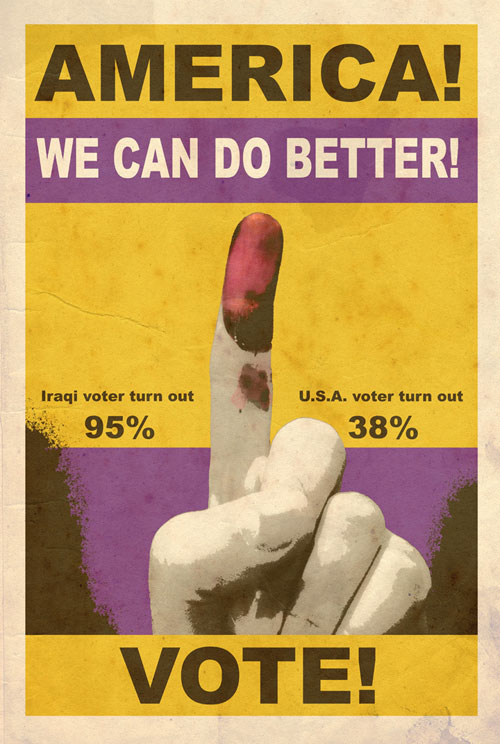

Implementing such a standard may not be easy, but it is not impossible. It begins with American citizens understanding original intent, voting for public officers based on this criterion, and demanding Federal supreme and inferior court judges are impeached if they unrepentantly cross this line in their opinions.

Elected officials will usually do what the majority of their voting constituents demand, therefore if voters from a simple majority of congressional districts across the nation demand their Representative impeach Federal judges, the Representatives will. Additionally, if voters in enough States demand their Senators convict an impeached civil officer, the Senators also will. This would send a very loud and clear message to Federal judges to stop legislating from the bench and to uphold constitutional original intent.

It is time “We the People of the United States” hold our elected and appointed officials to this rigorous standard. We must do this even when we individually do not like the outcome an original intent interpretation provides. Doing anything else will undermine our Republic and either turn us into a democracy, in which we are subjected to the tyranny of the majority, or it will allow the few to impose their will upon the rest, by which we will be subjected to the tyranny of the minority.

CDR Matthew W. Shipley, graduated from Navy recruit training in January 1985, Electronics Technician “A” School in October 1985, Naval Academy Preparatory School in 1987 and the United States Naval Academy in 1991.

Shipley’s tours include Assistant Platoon Commander at SEAL Team EIGHT, test article Officer-in-Charge of a Mark V Special Operations Craft (SOC) at United States Special Operations Command, Operations Officer at Special Boat Unit TWENTY, Mk V SOC Liaison Officer to Special Operations Command European Command, Naval Special Warfare Task Unit (NSWTU) Commander for a Mediterranean Amphibious Ready Group, and Platoon Commander at SEAL Team EIGHT.

As a reservist, Shipley served as Executive Officer of Navy Reserve Naval Special Warfare Group TWO Detachment 309, as Executive Officer of SEAL Team THREE deployed to Fallujah, Iraq in 2006, as NSWTU Commander Manda Bay, Kenya in Oct 2006 – Mar 2007, and as the Commanding Officer of SEAL Unit EIGHTEEN in Little Creek, Virginia from Dec 2009 – Dec 2011. He retired from the US Navy in Jan 2013.

Shipley’s awards include: Bronze Star Medal, Meritorious Defense Service Medal, Joint Service Commendation Medal, Navy Commendation Medal, Navy Achievement Medal and various unit, campaign and service awards.

5 Judicial Myths

Restoring a Constitutional Judiciary

by David Barton of www.wallbuilders.com

This presentation deals with several attitudes that have developed in recent decades toward the judiciary; and they’re really attitudes that, although very popular and we hear a lot of about them today, really have no constitutional basis in the way they’re applied. So in looking at these five judicial myths, I want to begin by going back to a statement made by George Mason.

George Mason was the founding father who was one of those who framed the Constitution of the United States. He, after leaving the Constitutional Convention, went home and really pushed for a bill of rights; the first 10 amendments we now have added to the Constitution. But he believed there needed to be some limitations on the Federal government to protect the rights of individuals. So he was particularly active in Virginia, and others picked up the same mantra of protecting individual rights and you saw movements pop up in North Carolina, Massachusetts, and elsewhere; but because he was one of the leaders in that effort, he is known as the Father of the Bill of Rights. He is also a primary author of the Virginia Constitution of 1776. And in that Constitution, George Mason made a statement that is so profound that it has been maintained in the Virginia Constitution to this day.

The statement he made is this. He said, “No free government nor the blessings of liberty can be preserved to any people but by a frequent recurrence to fundamental principles.” Now that’s a profound statement. He said you can’t have free government and you can’t enjoy the blessings of liberty unless you will go back and frequently remember the fundamental principles and preserve those principles. So, going back and looking at fundamental principles is what we’re going to do. And we’re going to specifically look at fundamental principles surrounding the formation of the judiciary.

Now when you look at the idea of judiciary and judges, this has become a very popular topic in recent decades. A number of books have been written about judicial activism, restraining overactive judiciary, ways to deal with judicial activism, and we see judges intruding in virtually every aspect of life; and sometimes we lament, ‘if only the Founding Fathers had done something to take care of activist judges.’ And we act as though this is a brand new problem, but it’s not. Activist judges were a problem in their day.

As a matter of fact, as part of the British colonies leading up to the American Revolution, there were a number of actions taken by British judges that really set off the Founding Fathers and started shaping their idea about what judges should do and should not do and what a judiciary should look like. As a matter of fact, if you go to the time of the separation from Great Britain to the time of the Declaration of Independence, as we study that document today we are very often told that the primary idea behind the separation of America from Great Britain was that these guys, the Founding Fathers, just did not like taxation without representation and that’s why they separated. And to a degree that is true. They did not like taxation without representation, but that’s not just the reason they separated.

In the Declaration, they gave us 27 reasons why they separated from Great Britain. The issue of taxation without representation is issue Number 17 out of the 27; it did not even make the top half of the issues that they listed. So, it was a concern, but to say that that was the driving concern is not accurate. When you read the Declaration of Independence, what you will find is a number of grievances including four grievances that deal with judicial abuses. Four of the 27 grievances, they said, look, we have really got trouble with the judges are being operated here in America with what the British judges have done; and this is a reason for separation is we just cannot get this judicial thing solved, and it needs to be solved. So judicial activism was a big problem to the Founding Fathers. It was something that specifically was part of the reason why they separated and, therefore, they did much writing about it.

Now to this day, 200 plus years later, we still find activist judges to be a problem. As you look across the various areas where we see judicial activism, man, you can see judges running things from criminal justice to military issues, to the laws and policy of a Congress, to moral issues, to religious issues, to educational issues. You name it; judges seem to be involved in it. And particularly in the area of religion, the Americans do not like judicial activism.

I find it striking that a recent poll that has come out says that 77% of the nation believe that judges have gone too far in removing religion from public life. Now that’s very profound. I mean, there’s very few things where you get 77% of Americans to agree on anything; and yet 77% of Americans agree that judges have gone too far in removing religion from public life.

And that same poll said that 59% of the nation believes that judges have singled out Christianity for attack. Now that’s a profound sentiment because usually you find that within the press and the media they tend to be more secular and not particularly friendly or sympathetic to Christian or biblical values; so they really don’t talk about all the losses that Christians seem to suffer in the courts. And yet, despite the fact that the media does not cover this aspect of judicial activism, there’s still enough out there. The 59% believe the judges have singled out Christianity for attack, and 77% they believe they’ve gone too far in removing religion.

So, this issue is still an issue today – judicial activism. But you’ll find that particularly in the 10 years leading up to the American Revolution, it was a focus of many Founding Fathers including Samuel Adams. Samuel Adams is called the Father of the American Revolution; and as early as 1765 he started pointing out two fundamental themes that were problems with the British judicial system that needed to be fixed in America.

Now the two things that he pointed out: And he said, ‘Number one, these judges have lifetime appointments, and that is not good. What we have, judges that once the King puts them there, we can’t remove ‘em, we can’t do anything with them. They’re there as long as the King’s alive.’ And he said the second problem with the British judicial system is there’s a lack of accountability. The King appoints these judges in America and they make all sorts of rulings and these rulings oftentimes are against the will of the people; and we can do nothing about it. We don’t have any way to control these judges. There is no accountability of the judges to the people, and this is a terrible way to have the judicial system.

So the two themes that Samuel Adams emphasized again and again were the themes of lifetime appointments, that’s a bad deal for judges; and lack of accountability, that’s a bad deal for a judicial system. Therefore, as you approach the Declaration of Independence, and they take and write four clauses dealing with judicial abuses, they’ve been talking about this for a decade, that they know what the problems are.

Now significantly, as they separated from Great Britain, that separation through the Declaration of Independence really renounces all the British government across America. This gives them the opportunity to go into their own colonies, or now their own states, and create their very first state constitutions. So as you look across the 13 colonies, you will find that these state constitutions, they start writing them in 1776 and 1777, and 1779, and 1780, that they’re writing constitutions to create their very first state government.

Now as they look at creating their state government, they’re very cognizant of the flaws that they have seen for the past several decades with the system under which they’ve been governed. They don’t want the problems they’ve seen with the British system; they want to do it right. And so, as you look into the state constitutions and look at how they’re approached, particularly the issue of the judiciary – what was their view of judges in the proper role of judges? Well, we’re going to see as they create their state constitutions because they’re going to tell us what they think judges should do, and that’s what they’re going to put in their system.

A great example of this is if you go to the Massachusetts Constitution. Now, the Massachusetts Constitution was written in 1779, it was adopted in 1780; and the Massachusetts Constitution is the only constitution in the world that is older than the US Constitution. The American government operates under the US Constitution; and we have the longest ongoing constitutional republic in the world but we don’t have the oldest constitution in the world. The Massachusetts Constitution written in 1780 is still in use today in Massachusetts.

Now that constitution was written by a number of the Founding Fathers who had signed the Declaration, and names that you’d immediately recognize that were real leaders in writing that constitution include: Samuel Adams, the Father of the American Revolution; John Adams who became President of the United States; and John Hancock, the President of Continental Congress. These were primary forces behind the writing of this oldest constitution in the world. In fact, John Adams himself is the one that wrote the cover explanation that went to the people of Massachusetts to tell them here’s the constitution we’ve come up with, here’s what we were shooting at, here’s the objectives we had, here’s what you need to know about the constitution. So Adams really is probably the primary face on this document; and he’s joined there with Sam Adams and Robert Treat Payne and John Adams.

Now so many others that are significant founding fathers… if you look inside the Massachusetts Constitution, you will find that it contains a Declaration of Rights. This is essentially a bill of rights on the state level. The Declaration of Rights in that constitution says all right, we’re setting out certain rights, and these are rights that the state government cannot get into. We’re setting out fundamental principles that cannot be violated by state government. And as you look at Article V of the Declaration of Rights of the Massachusetts Constitution, this is what it says. It says, “all power residing originally in the people and being derived from them, the several magistrates and officers of government vested with authority, whether legislative, executive or judicial, are their substitutes and agents and are at all times accountable to them.” Now get this, they say in this constitution that all power comes from the people and is derived from the people; therefore, all three branches of government that have any authority whether it’s legislative, executive, judicial, the people in those branches are the substitutes and the agents of the people themselves and are at all times accountable to the people.

Now, grab that. They say all three branches are accountable to the people. Today we hear, oh, no, no, no… judiciary, it’s an independent branch, it has to be separate from the people so it can’t be touched by political considerations and motivated by political… That’s not what the Constitution says. It says, ‘all power comes from the people and all three branches have to be accountable to the people.’ You see, it had been the opposite under the British system. They’re trying to fix it. They don’t want judges the way they’d had it in the British system.

Now that’s what you find throughout the state constitutions including the ones like Massachusetts that are still in use today. From those state settings, the Founding Fathers gathered some 11 years after the Declaration to write the Federal Constitution. They came to the Constitutional Convention first to revise the Articles of Confederation, realized that was a failure, so let’s just write a new document. And so as they began to write a brand new document for the federal government, delegates at the Constitutional Convention such as James Madison, who’s called the Father of the Constitution, and Charles Pinckney, these guys said specifically they relied on the ideas in the state constitution as they wrote the Federal Constitution. And why not? We’ve created brand new governments in the states, we have had them for more than a decade now, we have figured out what is right and wrong, even in our philosophy over the decade, and so now as we bring delegates from these 13 states together and we have their state constitutions, we know what works and we know what doesn’t work.

And so, as they draft the US Constitution, they are very cognizant of the very things that they had tried to avoid when they drafted their state constitutions. As a matter of fact, if you want to understand the US Constitution, one of the best ways to do it is go read the Declaration of Independent. Because, in reading the Declaration of Independence, you’ll find that they raised those 27 grievances; 27 things that they thought were wrong with the way that British were governing us.

But they saw those grievances in the Constitution; for example, the issue of taxation without representation. Well they didn’t think that was a good principle so, therefore, in Article I, Section VIII, they made it really clear that only the Congress of the United States can lay taxes. The Senate can’t and the President can’t. It has to be the representatives of the people. Therefore, no tax can be imposed on America unless it’s done by the representatives themselves. With that provision, you have just eliminated taxation without representation.

If you were to take the Declaration, and you get to grievance Number 4, and you say, all right, grievance Number 4, this is a problem – where did they fix it? Well, if you go over to the Constitution, Article I, Section V, paragraph four, they fixed the grievance that they raised in grievance Number 4. If you look for example at grievance Number 5, you say, now, grievance 5 in the Declaration, where did they fix that? You go for Article I, Section IV, paragraph two of the constitution. That’s where they fixed it.

If four of the 27 clauses in the Declaration dealt with judicial abuses, things they did not want to see the judiciary do, all you have to do is go to the Constitution and look at what the Constitution says about the powers of judiciary, and also look where the Constitution is silent. Look at what it did not say. And this is where we discover the five judicial myths. There are five ideas that are out there today that we popularly hear about the judiciary. Attorneys will tell us this, judges will tell us this, it’s in some civics textbooks, you’ll hear in the radio, you’ll hear people repeat it to one another; and yet when you go back and say now, wait a minute, show me where that is in the Constitution, you go, my goodness, it’s not there. I thought it was there. I was always told that was what judges were to do.

Myth Number 1 that we hear very often today is that the three branches of government are co-equal. Now, if you want to find sources that say that, you need to go no further than the Supreme Court’s own web site. If you go to the US Supreme Court web site, you will find this quote; it says, “The framers of the Constitution created three independent and co-equal branches of government.” By the way, they say it’s independent and co-equal; and we’re going to look at both those concepts. But let’s take the co-equal aspect first.

Supreme Court says we have co-equal branches of government. With the Founding Fathers agree with that? If they read that on the web site today, would they say, now wait a minute, where did you get that philosophy; or would they say, that’s exactly right, that’s what we said. Well, one of the best ways to know what they said and what their philosophy is, is to back, number one, read the Constitution; number two, read the Federalist papers. Now the Federalist papers were written while the ratification of the Constitution was underway. They finished the Constitutional Convention and now the delegates who signed the Constitution have returned to their home states; and really, the Federalist papers became a guideline for all the delegates to say, now remember when we went through and did this clause, this is what we were intending to do and you can explain this to your State Convention, your Ratification Convention, to help them understand the Constitution.

So the Federalist papers were written by three of the major Founding Fathers: James Madison, John J. Alexander Hamilton; and according to James Madison, this is what he said about the Federalist papers. He said, “The Federalist may be fairly enough regarded as the most authentic exposition of the heart of the federal Constitution as it was understood by the body which prepared it and the authority which accepted it.” In other words, what he said is the Federalist - this is the best source for understanding the intention of the body who wrote the Constitution and of the bodies who ratified the Constitution. If you want to know what they intended when they wrote it and ratified the Constitution, you read the Federalist papers because it goes through and explains all the clauses.

Now, when we do that, we can look into Federalist 51; and Federalist 51 deals with the legislative branch. And by the way, when you just go to the Constitution and read it, the first three Articles of the Constitution deal with the first three branches. Article I deals with the legislative branch; Article II with the executive branch; and Article III with the judicial branch.

When you look at Article I, it is really, really, really, really long. It’s the longest part of the Constitution; it lays out all the things that Congress can do and all the powers it has and all the responsibilities it has, just a ton of stuff. Article II is much, much, much shorter and it lays out what the President can do. But the shortest article of the three, and I mean shortest by a long way, is Article III, which lays out judicial powers. Very few things are judiciaries allowed to do. And that’s what the Federalist points out.

Federalist, in discussing Article I, that the Congress, legislative powers… this is the quote from Federalist 51: “The legislative authority necessarily predominates.” Now, notice that word predominate. Predominate does not mean co-equal. Predominate means one is over the other two; and that’s further affirmed when you go to Federal 78. And Federal 78 is one of the Federalist papers that deal with Article III and the judiciary. When it looks at the judiciary, which is the shortest article of the three in the Constitution, it says “The judiciary is beyond comparison the weakest of the three departments of power.” Now, Federalist 51 says the legislative is predominant; and Federalist 78 says that the judiciary is absolutely the weakest. And the Federalist paper goes on to say, 78, it said is so weak “the general liberty of the people can never be endangered from that quarter.”

Now, would we agree with that sentiment today that the judiciary is the least dangerous to the rights of the people? I think the judiciary is what’s messing up the right of free speech, the right of Second Amendment to keep and bear arms; it’s what’s messing up the right of private property and the Fifth Amendment. Judiciary seems to be where we get more encroachments on our rights than in any other branch. And no branch is perfect; and they’re going to make mistakes. But the deal is, with the other two branches, you can correct the mistakes in the next election. But the judiciary, when it tramples on a right, it’s more dangerous because it takes a long time to get rid of the judges that are there. But they designed it where that wouldn’t be the case. They designed it so that the judiciary would be absolutely the weakest, beyond comparison the weakest, and is so weak that the general liberty of the people can never be endangered from that quarter.

Continue when you read from Federalist 78, it says “The judiciary has no influence over either the sword or the purse, no direction either of the strength or the wealth of a society and it can take no active resolution whatever.” It may truly be said to have neither force nor will. Whoa. Did I just hear the Federalist say that the courts aren’t allowed to have influence over the sword or the purse, that they can’t have anything to say about what’s happening with military operations? I thought they were telling us what we had to do with terrorists and what we had to do with detainees and where we could have military tribunals, and where we had to give certain Bill of Rights rights to those who are combating the nation. Article I of the Constitution gives to Congress the sole authority to manage land and sea forces and the issues related in international law. It doesn’t give that to the courts; it gave that to Congress. Well, that’s what the Federalist says here as well.

It says the judiciary has no influence over the purse. Well, we just had a ruling where the court said, hey Congress, you have to expend this money; you’ve appropriated this money for this group, you have to expend it and you can’t cancel the appropriation. Now you got the courts telling Congress what they have to spend money on? That was never designed; they’re not supposed to have influence over the purse. It says they’re to have no direction either of the strength or the wealth of society; they can take no active resolution whatever. Really. Man, we talk about judicial activism all the time; but yet the Federalist paper said they were to take no active resolution of any issue whatever, that they’re not to be an activist branch, period. And that’s the way it’s designed.

Now when you look back on those two Federalist papers by themselves, one says the legislative authority predominates, the other says judiciary is beyond comparison the weakest, there’s no way you can read the Constitution or the commentaries on it and say we have three co-equal branches. And the Founders knew that. As a matter of fact, when you look at founders like William Giles – and William Giles is a very famous Founding Father, we don’t hear much about him today, but he was one of the original members of the First Congress, he is one of the framers of the Bill of Rights; as a matter of fact, he served in Congress under George Washington, under John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison, he became the governor of Virginia – but William Giles is also one of the authors of the original Judiciary Act.

Now the Judiciary Act, once the Constitution’s in place, the Constitution says okay, you can have judiciary, but Congress gets to set it up. So he’s one of the authors of what judges can and can’t do under the Constitution. Real simple stuff.

And this is what he says when you look over Article III of the Constitution, Article II, and Article I - you look at all three branches and what the Constitution says about the judiciary and what the other branches can do with it, this is what he said. He said, he said “Superficial observers take it for granted that the three departments of the government are coordinate and independent of each other.” It’s to be observed that the words coordinate and independent are not to be found in any part of the Constitution.

Now what he’s saying here, he says, people look at this. And they sometimes think, oh we have three co-equal independent branches. He said that’s a mistake. He said you can’t find the word co-equal or independent in any part of the Constitution. Now he continues; he says, “According to the Constitution, the establishment of the judiciary department was entrusted to the legislative department.” Is the judiciary department formed by the Constitution? It is not. It is only declared that there shall be such a department; it’s directed to be formed by the other two departments who owe responsibility to the people. He said when you read the Constitution, the Constitution does not establish the judiciary. It just says there’s going to be one.

As a matter of fact, you read Article III, the only court it says that we have to have constitutionally is a supreme court. It doesn’t tell how it operates; it doesn’t tell us how many judges. It doesn’t say anything about any courts below that except it calls them inferior courts. A district court or court of appeals are all inferior courts, and it says Congress can set them up however it wants to. It can have as many or as few as it wants, it can do whatever jurisdiction it wants. All the Constitution says is you have to have a judiciary.

Now when it comes to the President, when it comes to the Congress, the Constitution’s very explicit in how it has to be set up. Congress has to have two bodies; it has to have a House and it has to have a Senate. It tells us about the qualifications. You can’t be a House member unless you’re 25 years old; you have to be 35 years old to be a Senator; it tells us about residency requirements; it tells us about all sorts of stuff. It tells us how to have representation. We have to have so many people in every district. So, there’s a lot of specifics about the House and the Senate; although there’s some latitude. But there’s nothing like that for judiciary. There’s nothing that allows the judiciary to set itself up. It just says, all right, we’re going to have a supreme court, and President and Congress, you guys can set it all up and fix it however you want to; it’s up to you all. And that’s why the President can nominate, but it takes the Senate confirming a judge before they even get there. And by the way, that was only at that point for the Supreme Court; Congress could decide if they wanted anything other than the Supreme Court.

So, understanding that, here’s what William Giles said, going back to his quote. He said, “The number of judges, the affirmation of their duties, the fixing of their compensations, the fixing the times when and the places where the court shall exercise their functions, all these are left to the entire discretion of Congress.” Congress can postpone the sessions of the courts for eight or ten years and establish others to whom they can transfer all the powers of the existing courts. Judiciary, constitutionally, cannot even run itself. It takes the other two branches to run it, so how can it be a co-equal branch when it can’t even organize or run itself?

As a matter of fact, let me just go back to this quote by William Giles. Last part of his quote he said, “The spirit as well as the words of the Constitution are completely satisfied provided one Supreme Court be established.” All the Constitution requires is that you have a supreme court; it doesn’t tell you how many justices, doesn’t tell you how long it meets at all. Every court below that is called an inferior court. So, Congress could look out toward the western part of the United States, toward the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, or as some people call it the Ninth Circus Court of Appeals, it’s the most overruled court in the land; that court has jurisdiction over some seven states and about 59 million Americans, and they are wrong on so many cases, at least in the opinion of the US Supreme Court who regularly overturns them.

Look at Congress and say you know, we are tired of the nonsense that goes on out in the federal judges in California and Nevada and Utah and all that – we’re tired of that, we’re going to abolish the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. We’re not even going to have a Ninth Circuit out there. Any issue that’s out there, just take in onto the Supreme Court. No Court of Appeals. Congress could do that; there’s not a problem doing that. As a matter of fact, they could abolish the Ninth Circuit this afternoon at four o’clock, and tomorrow morning at ten o’clock, they could pass a bill that says, all right, we’re going to establish a brand new Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals; we’re going to call it Ninth Circuit Part B, and all these other judges that were judges yesterday aren’t judges today anymore. Now we’re having a brand new circuit and we’re going to have brand new judges. So, we’re going to start from scratch, all those guys are gone, we’re going to put new guys…

Congress can do that. It has the authority constitutionally to do every bit of that, and that’s what the Founders understood and that’s what the Founders talked about. That’s what William Giles tells us, and that’s what the Constitution tells us. Now, there are still several people today who understand this. One who understands this is a member of Congress, representative Steve King from Iowa; he’s part of the Constitution caucus and the Congress. There are some good guys in Congress who do get this. I’ve worked with a number of them in Congress but I love the way that Steve summarizes it. It sounds just like one of the Founding Fathers, it sounds like William Giles and Jefferson and others. This is what he says, “Constitutionally, Congress can reduce the judiciary to nothing more than Chief Justice Roberts sitting at a card table with a candle.” And that’s exactly right; Steve’s right.

Congress can say, you know, the only thing we have to have is a Supreme Court and we’re not even told how many justices it has to have. So we’re going to eliminate the Supreme Court down to just one justice and that’s going to be Chief Justice Roberts and he’s not going to have any staff, we’re not going to appropriate staff for him; it’s just him sitting at a card table with a candle, and that’s the entire judiciary. That can be done constitutionally, and the Founding Fathers put that power in the hands of the elected branches to make sure that the judiciary would also be accountable to the people.

So the first myth that’s out there of the five myths is that the three branches are co-equal. No, that is not constitutionally accurate; that is not historically accurate in the view and the writings of the Founding Fathers or in the writing of commentaries like the Federalist papers.

The second myth is somewhat related to that. And that is that the judiciary is an independent branch. Let me go back to the Supreme Court web site and read that quote again. Here’s the quote from the Supreme Court web site. The Supreme Court says, “The framers of the Constitution created three independent and co-equal branches of government.” Yeah, they wish. I mean, that’s why they have this up on their web site. They would love to have people believe that because the Founding Fathers did not create three co-equal branches of government.

Yeah, but didn’t it create three independent branches of government? Well, let’s look at that for a bit. And by the way, let’s think about the implications of what that means. If we have an independent branch, if the judiciary’s an independent branch, what does that really mean? Well, let me go to the American Bar Association web site. And the American Bar Association, this is the group of legal guys that certify law schools and say here’s the curriculum you have to teach, and here’s what you have to know to be a lawyer; and this is also the group that once the President, nominates an individual to be a judge, they will rate that individual and say well he’s well qualified or not qualified or whatever to be a judge, and Congress will consider that. So, here you have this outside private group that really does set the legal standards in America and even does a lot with deciding whether a judge should be appointed or not.

But this is what this legal group says about judicial independence. Here’s their quote: “Judicial independence is freedom from direction, control, or interference in the operation or exercise of judicial powers by either the legislative or executive arms of government.” In other words, judicial independence, independent judiciary, means that it’s free from the other two branches; they don’t have the right to direct, control, or interfere in the operation or exercise of judicial powers. Well, that sounds reasonable and logical. Isn’t that what we want? We want an independent branch there. Well let’s think about that for a minute.

Now this is part of the argument; that we have three independent branches of government. So if judicial independence means that the judges (judiciary) is free from interference or control (by) the other two branches, then let’s talk about how that would apply with something like legislative independence. Let me just take the same quote they had on independence, and I’m just going to substitute the word legislative for judicial. Now, here’s what it would say at this. It would say legislative independence is freedom from direction, control, or interference in the operation or exercise of legislative powers by either the judicial or executive arms of government.

In other words, Congress can do what it wants and the judges and the President don’t have a right… and the judges say, wait a minute, we’ve got the right to tell Congress what’s constitutional or not. Wait a minute; I thought you said independence meant that you were free from any interaction and free from control by the other branches. So judicial independence means you don’t want Congress to have any control over you but that means that you do want to have control over Congress. You want to be able to tell Congress and the President what’s constitutional or not but you don’t want them to do the same thing back to you.

Already, the concept that we have three independent branches doesn’t make sense. If they were independent, then certainly the judges would have no authority, no right to tell Congress what to do and have no authority, no right to tell the President what to do. So by logic, that doesn’t even hold up.

But nonetheless, let’s go back to this concept: do we have three independent branches? Going back to William Giles who helped author that original judiciary act; he’s already talked about the co-equal aspect. But listen to what he said about the independent aspect. He said, “They tell us they can see in the Constitution and they call on us also to see written therein in large capital letters the indefinite independence of judges which to the extent they carry the meaning of the term, is neither to be found in the letter or the spirit of that document.” Now he’s saying these people who want the judges to have so much power, they say now, in the Constitution, it’s in there, independence of judges, it’s in there. And they said, it’s not in there; and to the way that they mean it, he said there’s nothing in the spirit of the document that even has what they say it means.

And that’s what I was pointing out. If we’re going to say independence of judges meaning that the judges can control Congress and the President but not vice versa, there’s nothing in there like that. And he continues. Giles says, “With respect to the word independent as applicable to the judiciary it is not correct nor is it justified by the Constitution.” He says, “An independent department of a government is conceived to be a department furnished with powers to organize itself and to execute the peculiar function assigned to it without aid.” Or in other words, it’s independent of any other department. A moment’s attention to the Constitution will show that this is not the constitutional character of our judicial department. Well that’s it.

Again, this is a branch that can’t even organize itself, so how can it be an independent branch? If it wasn’t for the other two branches, the judiciary would not even exist except for just a Supreme Court; and all you need there is one Chief Justice and that’s it. So, judiciary’s not independent. It relies on the other branches for its salary, for its staff, for its jurisdiction, knowing what states it has, knowing what issues it can deal with, knowing the term of a… all that comes from the others. It’s not independent. They just want to be independent. They want no to tell them, no one to make them accountable for what they do. And they want to be able to tell the others that.

Now see, the Founders never envisioned that. A great example is John Dickinson. John Dickinson is a signer of the Constitution; and John Dickinson, in considering that we might have an independent judiciary, that was a nightmare to him. Listen to what he said. He said, “What innumerable acts of injustice may be committed and how fatally may the principles of liberty be sapped by secession of judges utterly independent of the people.” And he’s right because if you have independent judges, if there’s no accountability for them, if the other branches can’t interfere and say wait a minute, you guys are off the reservation, we’re not doing it your way, you’re out in left field somewhere and you’re just wrong, we’re not doing that; if you can’t do that, then what are the principles of liberty? You’ve now given into an unelected body to have all the final say on what the other branches do. That’s not liberty; that’s not representation of the people. That’s why they objected to an independent judiciary.

Thomas Jefferson said the same thing. In fact, Thomas Jefferson, who was a supporter of Gideon, the Monarchy out of France; he wanted to see the people of France free from the King. After the Revolution in France, they asked him for recommendations on how to set up government and so he gave them this message. He said, now look, in America here’s how we do it. And this is what he told them. “We think in America that it is necessary to introduce the people and to every department of government.” Whoa, Thomas, you’re saying introduce the people into the judiciary as well? Absolutely; listen to what he says.

He said, “We think it’s necessary to introduce the people and to every department of government.” He said if I were asked to decide whether the people had best be left out of the legislative or the judicial department he said, in other words; if you’re going to ask me is it more important to have the people involved with the election of Congressman or with judges – and we say, wait a minute, how would you say citizens should not be involved in electing Congressman – well, there’s no way he’s going to say that. That’s an absurdity, and that’s why he used the example. He said we all know that the people elect Congress. He said, but if you’re going to ask me is it more important for the people to elect Congress or be involved with their judges, he said “I would say it’s better to leave the people out of the legislative branch than out of the executive branch.”

He said the execution of the laws are more important than the making of them. In other words, we can elect people to Congress and they make the laws, but if we don’t have influence and control over judiciary, they’re the guys that interpret the laws, and if there’s no citizen input there, if there’s no accountability, then what good does it matter who you elect if the judges have the power to make it anything…?

You can elect a Congress that says we firmly believe that two plus two equals four. Well, if Congress says two plus two equals six, we can throw them all out in the next election. But let’s say that Congress passes a law that says two plus two equals four and the judges look at the law and say, no we’ve determined that two plus two equals five. Well, if there’s no ability of the citizens to get in and make the judges accountable, then is it really important to make the laws or to interpret the laws?

Clearly interpretation; and that’s why Jefferson said you can’t leave the people out of any branch. He says as important as it is to elect people to Congress, it’s even more important to have citizens involved in the judicial branch because that’s where the laws are interpreted after they’re made by the Congress that people elect. So this is what Jefferson understood. Now, it was so clear that he gave this profound statement. Let me just read this from Jefferson, it’s great. He says, “It should be remembered as an axiom of eternal truth in politics that whatever power in any government is independent is absolute also, independence can be trusted nowhere but with the people en masse.”

Now grab this. That is if a power is independent, it gets the final word. And do we really want an independent judiciary? Do we want them to be absolute? Do they get the final word? No, we don’t want independent branches. We want three branches that derive their power from the people and that are accountable to the people; and that means that we have to be able to get at the judges through the President and through the Congress which is what the Constitution allowed. The people have access of all three branches and control over all three branches unless we buy into these myths that say well there’s nothing we can do about it, they’re independent judges, and judiciary’s an independent branch, and it’s a co-equal branch, and that’s just the way the Founders made it. That’s not the way the Founders made it.

And by the way, even though we’re talking about judiciary, that axiom by Jefferson is profound. Again, here it is. “It should be remembered as an axiom of eternal truth in politics that whatever power in any government is independent is absolute also.” You know, that applies not only to the judiciary; that applies to bureaucracies; that applies to agencies; that applies to groups like the IRS. I mean, they are such a bureaucratic nightmare that you can’t find ways to make them accountable. And if they decide to come after a citizen, the citizen really has no way to make them accountable. They are such a huge agency with such a big budget and so many paid government attorneys as opposed to my little income that I might have as a citizen, it becomes a tyranny. And that’s why every single aspect of government was to be made accountable. And it doesn’t matter whether it is an agency or a bureaucracy or a judiciary; it cannot be independent from the people. It cannot be unaccountable to the people.

So, that is the second myth. The second myth is that the judiciary is an independent branch. No, that’s not what the Founding Fathers said and they did everything they could to tell us otherwise.

The third myth that’s out there says well, judges are the ones who determine constitutionality of laws, and the primary way that they do that is by judicial review. Now it is true that judges, under the Founding Fathers, were allowed to determine constitutionality of laws; but it is not true that the way that they did that was judicial review in the sense that they have the final word on constitutionality. They’re allowed to give their opinion, and we’ll talk about that in a moment, but let me give you some examples of how the courts and how others talk about this particular myth.

Now again, the myth is that only judges are able to determine what’s constitutional and the way they do this is primarily through a judicial review. So, let me go back to the Supreme Court web site because this is a great source of propaganda about the judiciary. The Supreme Court says this, “As the final arbiter of the law the court functions as a guardian and interpreter of the Constitution.” Now, that’s a profound statement; that they are the final arbiter of the law. They get the final word on whether law is constitutional or not.

As a matter of fact, I give a lot of tours of Washington, DC and whenever I take groups through the US Supreme Court and they did the tour, I have to take them outside afterwards and have a debriefing and say okay guys, did you hear what they just said in there? Because what they say on the tours of the US Supreme Court, they say this is the building from which all the law in the land emanates. Wait a minute – what is that big dome building across the street that they call Congress where they pass all the laws? And they say, no, no, no, no; this is the building from which all the law in the land emanates. Congress passes law over there but we get the final say on whether that law is a real law or not.

So the court itself considers itself the final word on all laws. Now, the way that they do this is through judicial review. And judicial review is not a new thing in America; but the way it is used today is a new way of doing it. As a matter of fact, when you look at this judicial review concept, Encarta encyclopedia says this. It says that the Supreme Court’s principle power is judicial review which is the right of the court to declare laws unconstitutional. Now if you look in law books today, if you look on on-line encyclopedias etcetera, they’re going to tell you that the power of judicial review was established in the case called Marbury vs. Madison back in 1803.

Marbury vs. Madison is a very interesting case, very interesting background; and this is what they claim today is the origin of the Supreme Court’s power to strike down laws and tell other branches what they can do. The Marbury vs. Madison case came out of the Presidential election of 1800. In the election of 1800, you had incumbent president John Adams running against challenger Thomas Jefferson. Now, John Adams was the founder of what was known as the Federalist Party; that was his party. Jefferson was the founder of an opposite party; the name of his party was known as the Anti-Federalist Party and it pretty much tells you how different the two parties were. One’s a federalist, the other’s the anti-federalist. In essence, well, whatever you guys believe, we’re against it. So if you’re federalist, we’re anti-federalist. And that is the type of animosity that existed between the two parties.

Now, in the election the people have a choice. They can endorse the philosophy of either one of these two parties by how they conduct themselves in the elections. And in the elections, the people overwhelming shows the anti-federalist party. They just cleaned out the House of Representatives, they cleaned out the federalists to a great degree; they switched the balance of power, they loaded it up with anti-federalists. And at the state legislative level and the state elections, they loaded the state legislatures up with anti-federalists. And since the state legislatures at that time got to appoint the US Senators, that now meant that the US Senators who have been appointed to the Senate or loaded up with anti-federalists and Jefferson gets elected as President as an anti-federalist. So now you have the anti-federalists having the House and the Senate and the Presidency of the United States.

Well, this is the election; and before the Constitutional Amendment changed the timing, you had a long lame-duck session of Congress and the President. In other words, from the time of the election to the time that Jefferson was sworn in as President, it’s going to be months. Well, in that months’ period of time, the federalists, stinging from their defeat, said well we need to entrench as much as we can of federal philosophy in here before the anti-federalists get in.

So, the House and the Senate, with the signature of President Adams, created a judiciary bill that birthed a bunch of new federal courts. They said we’re going to create a whole bunch of federal courts and we’re going to appoint federalist judges to those courts; and we’re going to load the courts up… we’re going to stack the courts with federalist judges. And that’s what they did. As I recall, I think it was 16 new judicial … and that was a bunch; that was doubling the size of judiciary. They created 16 new slots and they created slots in Washington, DC, the federal capital. And so they’ve created all these slots, the President then nominates judges to fill these slots, and the Senate has to confirm all the judges. So the Senate confirms the President’s judges, we’re loading this up with federalist judges.

And now there’s a commission to be given to each federal judge. You’re notified that you’ve been appointed by the President, you’ve been confirmed by the Senate, and here is your official seal on your commission; you are now a federal judge. Well, President Adams took those commissions and gave them to the Secretary of State and said now deliver these to all the judges, make sure that these guys get their judicial appointments; make sure we get all these federalists on the court before the anti-federalist administration, Jefferson and those guys, come in. So it gets to the Secretary of State and, for whatever reason, the Secretary of State forgot to deliver the commissions to all these judges. So when the next administration comes in, here comes President Thomas Jefferson, and his Secretary of State is James Madison. And of course, James Madison today is called the Father of the Constitution; so we can assume he’s a little bit of a constitutional expert anyway. And he gets there, and he’s Secretary of State for President Jefferson. And he looks on the Secretary of State’s desk and there he sees these commissions for all these judges; and he says, well I’m not going to deliver these things. I mean, we’re trying to reverse what the federalists did not extend it. I’m not going to deliver these commissions.

And one of the guys who did not get his commission was a judge in Washington, DC. He was a Justice of the Peace there; he was appointed, he was supposed to have one of these slots and he didn’t get it so he sued James Madison. And the guy’s name was Marbury, William Marbury. And so he sues Madison; and so the suit is named Marbury vs. Madison. Well this suit goes to the US Supreme Court. Now, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court then was John Marshall. John Marshall had been appointed by John Adams in the latter stages of Adam’s administration. He’s going out of office but he wants to fill the courts with federalist guys so he nominates John Marshall as the Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court, and the Congress confirms him. So now that this case with Madison and Marbury (who didn’t get his commission delivered) goes to the Supreme Court. And it’s in front of Marshall and the judges and they’re supposed to decide, well should the President go ahead and deliver these commissions that were given under the previous administration? That kind of sounds like it might be kind of a biased decision anyway; you know, the President stacking the court and this guy has a vested interest, John Marshall.

But aside from that, if you just think back over this scenario, if the Secretary of State had just remembered to deliver the commissions, what’s the issue? The problem was he forgot to deliver those commissions; and because he forgot to deliver the commissions, Madison found them and he refused to deliver them. So it really goes back on the back of the Secretary of State for John Adams. If the Secretary of State had done what he had been told to do, that’s the end of the issue.

By the way, who was the Secretary of State for John Adams? Oh, it was John Marshall. John Marshall was not only Secretary of State, he’s Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. This kind of sounds to me like we might have a little ethical problem here, maybe a little conflict of interest. You mean to tell me that John Marshall is about to rule on whether he should have delivered the appointments to these guys? And that’s the case now in front of him? You know, today we would demand that he recuse himself. You can’t do that. But he didn’t recuse himself, and so what he did was he issued a ruling. And his ruling was significant. He said first off, well, the Supreme Court really doesn’t have the authority to tell the President what to do. He said, but if we did have the authority, we would tell the President to deliver those commissions to the judges.

Well, when that ruling came down, and Marbury vs. Madison is the first time that the Supreme Court ever tried to tell another branch what to do; we’ve had the courts in 1789, and so here we are some 14 years later, and this is the first time the court has tried to tell another branch what to do, first time in 14 years. And when it happened, Jefferson went through the roof. He called it a perversion of the law. James Madison went through the roof; he flat ignored the decisions of the Supreme Court. How dare you try to tell the other branch… you don’t have the authority to tell the other branch what to do. And so that was a real scandalous time in the court. And you’ll find that even in John Marshall’s biography, his biographers kind of conveniently forgot to talk about the Marbury Madison… it was such an embarrassing thing. You know, he had forgotten to deliver the commissions; and now he’s put himself in an unethical position having to rule on it. So, biographies, the early biographies just passed by that, didn’t even talk about it.

But suddenly, as we get into this age of judicial activism and we forget our history, law schools look back and say, oh yeah, John Marshall, the Marbury Madison case. That’s the first use of judicial review and this is where the Supreme Court set the precedent of being able to tell the other branches what’s constitutional and what’s not. Well, that… in 1803 is when the Supreme Court tried to tell the President what it could and couldn’t do. But when’s the first time the Supreme Court used judicial review to strike down a law of Congress?

Significantly, that happened in 1857. The case in which the Supreme Court first struck down a law of Congress was called Dred Scott. Now you may remember the Dred Scott decision, it is one of the most infamous and notorious cases in Supreme Court history. It’s where the Supreme Court said that blacks, African Americans, they are not people; they are property. Famous quote from that case says that no black has any right which a white man is bound to respect; you don’t have to pay any attention to blacks, they are property, they are not people. And so, what law does the Supreme Court strike down?

Well they went… Now this is 1857, Dred Scott decision; they went back all the way to 1820. In 1820, Congress had passed a law called the Missouri Compromise. In the Missouri Compromise Congress said we will not have slavery in these territories. Well, the Supreme Court of 1857 backed up and said, hey that law you guys passed 37 years ago saying that you couldn’t have slavery in certain territories, that’s an unconstitutional law. Blacks are not people; they are property and you cannot abolish property from any territory. And so, you can’t abolish slavery anywhere.

Well, what you’ve got here is the Supreme Court; the first time it uses judicial review to strike down a law of Congress is in the Dred Scott decision, to say that Congress has no authority to limit slavery anywhere. We the Supreme Court have decreed it. Now, that was 1857.

The next presidential election was in 1860, and Abraham Lincoln was running for President. He won the presidential election, Republicans won the House and the Senate; they had campaigned in their platforms against the Dred Scott decision that if they got elected they’re going to ignore it. And that’s what the President said when he was inaugurated. He said, now some people think you should be bound by the decision of the Supreme Court; he said but if that be the case, then we’ve given up our elected government. We’re being bound not by what the people want but what those judges want. And so, as Lincoln comes in, he just promptly ignores all the things the Supreme Court had said in Dred Scott. They said you can’t abolish slavery anywhere; he promptly abolished slavery in Washington, DC. He followed it up with the Emancipation Proclamation. He started passing civil rights laws allowing blacks to serve in the military, allowing blacks to serve in juries; giving them equal pay for serving in the military that whites… he went through and started doing all the… It’s all unconstitutional, he can’t do that. Well, he just ignored the Supreme Court. That was separation of powers.

The Supreme Court was never viewed to have the final word over either branch, and that was understood all the way through. So people say to me today, but wait a minute, doesn’t the Supreme Court get stuff right? I mean, think about the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision. That’s when the Supreme Court banned and ended segregation in America. Didn’t the Supreme Court do something good then? I mean, isn’t it good for the Supreme Court to step in and make things right? Well, that’s an interesting question. Let’s look at that Brown vs. Board of Education.

You know, that decision by the Supreme Court to end segregation, it was a right decision; it was a good decision. You know, I remember pictures still, like little Ruby Bridges in Louisiana having to have federal agents escort her into school because of the racism. And you have in Little Rock where the nine students wanted to go to Central High School in Little Rock and you had to have President Eisenhower call out the National Guard; eleven hundred troops just to get those 11 black students into an all-white high school. It was good to… It was right to end segregation but there’s something that needs to be noted here.

When you go back to the end of the Civil War, the Civil War’s over and three civil rights Constitutional Amendments passed; 13th, 14th, 15th Amendment of the Constitution, establishing racial civil rights for former slaves, ensuring they have the right to vote and own property and keep and bear arms, and religion… all the rights, guaranteed - 13th, 14th, 15th Amendment. In that period of time in reconstruction, Congress passed 23 civil rights laws. Now, the one that I want to point to for just a moment is the civil rights law Congress passed in 1875.

In that law passed by Congress in 1875, Congress banned segregation in America. They said everyone is created equal, we’re endowed by our Creator, and these civil rights amendments we have just passed had just made everybody equal under the law. God’s already made us equal but now we’ve done it by the law; and as part of enforcing the 14th Amendment, we are banning segregation in the United States. We are banning it in dining, we’re banning it in transportation, we’re banning it in lodging. No segregation in America any more. Man, what a good move by Congress. We got rid of segregation.

The problem was that in 1882, the Supreme Court overturned that anti-segregation law. The Supreme Court said wait a minute, you can’t ban segregation; we think segregation’s a pretty good thing. Now grab this. The Brown vs. Board of Education decision was merely the Supreme Court reversing itself from 70 years earlier when it got it wrong. The Congress already had it right. Congress ended segregation in 1875. The Supreme Court struck it down. Their laudable decision to reverse segregation, Brown vs. Board of Education, was simply the courts catching up with Congress 70 years earlier.

The court is not the branch that protects the rights of the people; Congress is. The courts are behind so many times throughout American history. So going back to the Supreme Court web site, the court’s web site says as the final arbiter of the law… Now notice that. The court says we get the last word on every law. And the emphasis there should be as the final arbiter; we are the ones that get the final word.

Now, what if the Founding Fathers had heard a statement like that made? Well, amazingly, it was made 200 years ago. And when somebody had the audacity to raise such a ridiculous notion, James Madison went through the roof. He heard on the floor of Congress, somebody say oh no, the courts get the last word. James Madison, Father of the Constitution; here’s what he said. The argument is that the legislature itself has no right to expound the Constitution, that whenever its meaning is doubtful, you must leave it to take its course until the judiciary is called upon to declare its meaning. He said I beg to know upon what principle it can be contended that any one department draws from the Constitution greater powers than another and marking out constitutionality. He said, wait a minute guys; you show me any basis for saying that Congress that doesn’t have as much authority in determining constitutionality as the courts.

And by the way, I would say that Congress probably has a greater grasp of the Constitution. I mean, after all, they do take an oath to uphold it; but they are the ones that don’t just have an hour hearing before the Supreme Court case and some papers turned in. They’re the ones who have hearings on the issue. It goes to debate. It goes through vigorous debate. It goes through hundreds of guys saying, now wait a minute, have you thought about this. It goes through, as the Scriptures calls it, iron sharpening iron. It goes through a honing process over in the House and Senate, and the debates and the committee process; you’re more likely to reach what’s constitutional not over there with more minds talking about it than just having the best out of nine, the majority out of nine which could be five people saying, well we’ve thought about it and here’s what we think.

And by the way, to assert that only the Supreme Court can determine constitutionality, that you can’t know what’s constitutional unless you’re a Supreme Court justice, how ridiculous is that notion? I mean, we have a federal law that to this day requires that every September the 17th, on Constitution Day, that every public school in the United States have students read and study the Constitution of the United States. Man, we need to get rid of that law, because there’s no way a student can understand the Constitution. Even attorneys can’t understand it; only judges on the Supreme Court can understand the Constitution. My goodness. We start teaching the Constitution back in elementary school because it is such a simple document. It’s not hard to understand. The members of Congress, the President, they take an oath to uphold it. All they got to do is read it, and it’s real clear what’s there.

Somehow we’ve turned this notion into upholding what the judges say about the Constitution. That’s not the same thing as the Constitution itself. So, going back to James Madison, he said I get to know upon what principle it can be contended that any one branch draws from the Constitution greater powers than another and marking out constitutionality. He says nothing has yet been offered to invalidate the doctrine that the meaning of the Constitution may be as well ascertained by the legislative as well as the judicial authority. There is nothing that says that Congress can’t determine constitutionality; they are just as capable as anybody else. Anybody that can read the Constitution can determine constitutionality; it’s that simple of a document.

And that’s why when you look at decisions of the US Supreme Court to this day, when you look at the decision, right up top it’s going to say Supreme Court of the United States. It’ll give you the case, whatever the case name is and they just decided; and then when you get to the body of the text of the decision it starts this way. It says Justice so and so delivered the opinion of the court in which Justices so and so joined.

Now, but notice that. The court delivered the opinion of the court; it doesn’t say the law of the court. It says Justice so and so delivered the opinion. That’s all it was; it was an opinion. The court has a right to have an opinion. It has a right to review laws for constitutionality, it has a right to say you know, Congress, we’ve looked at this law and in our opinion, this law’s unconstitutional because it doesn’t do this, this and this. And Congress is going to say, you know what, we didn’t even think about that when we passed it; you’re exactly right. We’re going to go back and amend the law to include… All it is is the opinion of the court; it is not binding. It is not the law of the court. They do not make the law of the land. It’s an opinion, and you have the right to consult that opinion if you want.

Now, where the court’s decisions are binding is within the judicial branch itself. The court can say, hey, here’s policy within this branch. We can’t tell either of the other two branches what to do and we can’t overrule their decisions; but within the judicial branch, here’s how you’re going to empanel juries and here’s how you’re going to apply sentences, and here’s how you’re going to interpret the evidence clause. I mean, the judiciary has a proper right to say, within its own branch, what it can do; but to tell the other branches? No, no, no; you can’t do that. That’s why to this day it’s still called the opinion of the court.

When you look back at the Constitutional Convention, even those members of the Constitutional Convention who were great defenders of judicial review – and by the way, there is constitutionally nothing wrong with judicial review, that’s fine. Every branch, every citizen has a right to look at it and say hey, my opinion is that this is unconstitutional. That’s great. But does that make it binding on the others? No. The people have a right to make it binding on Congress and the President through elections. But the unelected branch doesn’t have the right to make it binding.

So, judicial review is a legitimate power. The Founding Fathers supported it but they drew a line at having the judiciary tell the other branches what it meant after judicial review. A great example is Elbridge Gerry. Elbridge Gerry, one of the guys who wrote the Constitution, is also one of the guys who helped frame the Bill of Rights; he’s a big proponent of the Bill of Rights up in Massachusetts just as George Mason had been down in Virginia. This is what Elbridge Gerry, who supported judicial review, this is what he said. “It is quite foreign from the nature of the judiciary’s office to make them judges of the policy of public measures.” Hey, we don’t let judges determine public measures. Now they can decide whether evidence is right and the jury was empaneled right and whether the law was applied fairly; but we don’t make them judges of the policies. That’s not within their jurisdiction.

Same thing was pointed out by Luther Martin. He’s another one of the guys who wrote the Constitution. He’s another big Bill of Rights guy over in Maryland; he helped create the Bill of Rights movement over in Maryland. He’s the Attorney General of Maryland. I mean, he is a legal expert. Founding Father Luther Martin said this. He said, “A knowledge of mankind and of legislative affairs cannot be presumed to belong in a higher degree to the judges than to the legislature.” He said you got to be kidding me. You think that judges know more about laws and lawmaking and process than the Congress does? He said that’s not true. So there was never an intent of having the judges tell the Congress or the President, either of the two branches, what the policy was to be.

Now that was made very clear by John Randolph. And John Randolph, early Founding Father, he served in six different presidential administrations; as a matter of fact, John Randolph is the first member of Congress to oversee the impeachment of a Supreme Court justice. A justice of the Supreme Court was impeached? Absolutely. And John Randolph is the one who led that impeachment proceeding. Now, John Randolph in considering the notion that the court might have the final word, he thought that was just unbelievably absurd. And this is what he said. He said if you believe that, he said “If you pass the law that judges are to put their veto on it by declaring it unconstitutional?” He said here is contingent for a new power of a dangerous and uncontrollable nature. He said, are you really saying that the judges can veto a law and declare it unconstitutional? He said if you’re doing that, then you’re giving a new, dangerous and uncontrollable power. He said, “The power which has the right of passing without appeal on the validity of laws is your sovereign.” Whoever gets the final word of laws and there’s no appeal from that final word, that’s your sovereign.

Now that’s why if Congress passes a law and we the people think it’s wrong, we can throw them out of Congress and change the law. We’re the sovereign; we get the final word on whether the law’s any good or not. But if you put it over to the judges, they pass a ruling and say well, we determine this law is not a good law, what recourse is there from that? You wait another 70 years until you get a new court and get a different decision? No. At that point, the judiciary has become your sovereign. That’s exactly what John Marshall pointed out. Thomas Jefferson agreed emphatically.

Jefferson said, “The opinion which gives to the judges the right to decide what laws are constitutional and what not would make the judiciary a despotic branch.” He said the Constitution on this hypothesis is a mere thing of wax in the hands of the judiciary, which they may twist and shape into any form they please. He said guys, if you’re going to say that the judges have the right to decide what’s constitutional and what’s not, not only does that make the judiciary a despotic branch, it makes the Constitution like something of wax that they can twist and shape into any form they please.

That’s why we did not have the viewpoint, and that’s why it is the third myth that only judges can determine what’s Constitutional; and they do that primarily through judicial review.

The fourth myth is that federal judges hold lifetime appointments. Man, we’ve heard that all of our lives. That’s in textbooks; federal judges have lifetime appointments. It may be in the textbook but try to find that in the Constitution. As a matter of fact, do you remember back to Sam Adams? One of the complaints raised way back in 1765 that went for a decade up to the Declaration; that they fixed in the Declaration of the State Constitution then the Federal Constitution, was lifetime appointments. John Adams said the two problems we got is lifetime appointment of judges and judges that aren’t accountable to the people. We’ve got to solve those problems, and that’s what they did.

Well, how did they solve the problem of lifetime appointments for judges? All you have to do is read Article III of the Constitution, very short. It says this, “The judges both of the Supreme and inferior courts…” Now remember, the Supreme Court is the only court established by the Constitution. Inferior courts is any courts that congress might decide. The Constitution says, “The judges both of the Supreme and inferior courts shall hold their offices during good behavior.” Whoa. That doesn’t say lifetime. How long can they hold their offices? During good behavior.